he

secession crises of 1861 and the Confederate bombardment of

Fort Sumter on April 12–13 had practical implications for

Joseph Henry and the Smithsonian, as it did for all of Washington.

On April 15, President Lincoln issued a proclamation declaring

that an insurrection had commenced. He called on the states

to send 75,000 volunteer militia to the unprotected capital.

Two days later in Alexandria a secession flag was hoisted atop

the Marshall House hotel in celebration of the Virginia state

convention in Richmond, which had just voted a referendum for

secession. This inauspicious flag was visible from the Castle

towers and the White House. On April 19, Southern firebrands

in Baltimore rioted when the 6th Massachusetts Volunteers, in

answer to Lincoln's call, passed through the city. Rebels cut

telegraph lines, isolating Washington from the North. For several

anxious days, residents and city authorities alike feared that

the capital would be attacked, “if not by the Southern

Confederacy,” wrote Joseph Henry, “by reckless filibusters,

who, taking advantage of a state of war, will endeavor to surprise

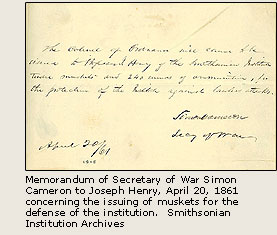

the city.” His opinion was reinforced by Secretary of War

Simon Cameron in a memo of April 20, informing Henry that the

colonel of ordnance would be issuing the Smithsonian 12 muskets

and 240 rounds of ammunition “for the protection of the

Institute against lawless attacks.” he

secession crises of 1861 and the Confederate bombardment of

Fort Sumter on April 12–13 had practical implications for

Joseph Henry and the Smithsonian, as it did for all of Washington.

On April 15, President Lincoln issued a proclamation declaring

that an insurrection had commenced. He called on the states

to send 75,000 volunteer militia to the unprotected capital.

Two days later in Alexandria a secession flag was hoisted atop

the Marshall House hotel in celebration of the Virginia state

convention in Richmond, which had just voted a referendum for

secession. This inauspicious flag was visible from the Castle

towers and the White House. On April 19, Southern firebrands

in Baltimore rioted when the 6th Massachusetts Volunteers, in

answer to Lincoln's call, passed through the city. Rebels cut

telegraph lines, isolating Washington from the North. For several

anxious days, residents and city authorities alike feared that

the capital would be attacked, “if not by the Southern

Confederacy,” wrote Joseph Henry, “by reckless filibusters,

who, taking advantage of a state of war, will endeavor to surprise

the city.” His opinion was reinforced by Secretary of War

Simon Cameron in a memo of April 20, informing Henry that the

colonel of ordnance would be issuing the Smithsonian 12 muskets

and 240 rounds of ammunition “for the protection of the

Institute against lawless attacks.”

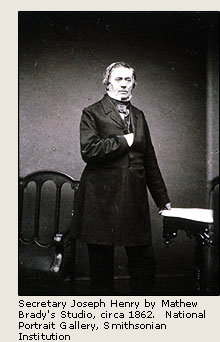

From

the beginning, Joseph Henry was confronted with the exigencies

of war. As a scientist, he had emphasized the need for the

institution to be apolitical and autonomous of government

interference. To demonstrate the institution's neutrality,

Henry did not fly the American flag over the Castle during

the conflict. He was criticized for this, and his patriotism

was questioned by some, but never by President Lincoln or

his administration. Henry believed that in the event of a

hostile attack, the institution might fare better if it flew

no colors at all, especially during that precarious spring

of 1861. Ironically, Henry’s immediate concern was not fending

off attacking Southerners, but coping with the influx of Yankees

seeking quarters in such public buildings as the Capitol and

the Patent Office. When authorities suggested the Smithsonian

as a temporary barracks, Henry argued instead that its use

as an infirmary would be “more in accordance with the

spirit of the Institution.” The War Department respected

his wishes and did not impose upon the institution. Still,

Henry proved to be a valuable asset to the administration.

He and President Lincoln personally liked and admired the

talents of the other, although their political philosophies

differed significantly about the wisdom of resorting to arms.

Henry believed that war was a mistake and that it would not

necessarily lead to a reconciliation between North and South.

Nevertheless, he placed himself and the institution at the

service of federal authorities whenever science could lend

a hand to the war effort. From

the beginning, Joseph Henry was confronted with the exigencies

of war. As a scientist, he had emphasized the need for the

institution to be apolitical and autonomous of government

interference. To demonstrate the institution's neutrality,

Henry did not fly the American flag over the Castle during

the conflict. He was criticized for this, and his patriotism

was questioned by some, but never by President Lincoln or

his administration. Henry believed that in the event of a

hostile attack, the institution might fare better if it flew

no colors at all, especially during that precarious spring

of 1861. Ironically, Henry’s immediate concern was not fending

off attacking Southerners, but coping with the influx of Yankees

seeking quarters in such public buildings as the Capitol and

the Patent Office. When authorities suggested the Smithsonian

as a temporary barracks, Henry argued instead that its use

as an infirmary would be “more in accordance with the

spirit of the Institution.” The War Department respected

his wishes and did not impose upon the institution. Still,

Henry proved to be a valuable asset to the administration.

He and President Lincoln personally liked and admired the

talents of the other, although their political philosophies

differed significantly about the wisdom of resorting to arms.

Henry believed that war was a mistake and that it would not

necessarily lead to a reconciliation between North and South.

Nevertheless, he placed himself and the institution at the

service of federal authorities whenever science could lend

a hand to the war effort.

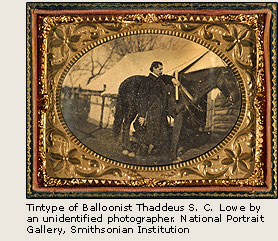

In

June 1861, aeronaut Thaddeus S. C. Lowe brought his balloon

to the Smithsonian for Henry's inspection and to make an ascent

to test the use of telegraphing from the air to the ground.

Henry supported Lowe's efforts to provide the Union army with

aerial reconnaissance. Likewise, he cooperated with Albert

J. Myer, the army's first chief of the signal corps, in testing

a system of lantern signals at night from the Castle’s highest

tower. In February 1862, Henry was named to a three-member

navy advisory commission to assist the government in assessing

such new scientific innovations as the design of ironclad

ships and new weapons. The board’s formal evaluations on hundreds

of proposals, many of them impractical, saved the government

from spending money on bad inventions. In

June 1861, aeronaut Thaddeus S. C. Lowe brought his balloon

to the Smithsonian for Henry's inspection and to make an ascent

to test the use of telegraphing from the air to the ground.

Henry supported Lowe's efforts to provide the Union army with

aerial reconnaissance. Likewise, he cooperated with Albert

J. Myer, the army's first chief of the signal corps, in testing

a system of lantern signals at night from the Castle’s highest

tower. In February 1862, Henry was named to a three-member

navy advisory commission to assist the government in assessing

such new scientific innovations as the design of ironclad

ships and new weapons. The board’s formal evaluations on hundreds

of proposals, many of them impractical, saved the government

from spending money on bad inventions.

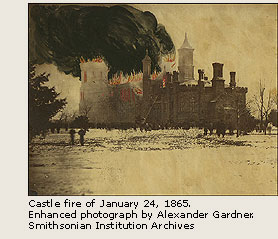

Throughout

the conflict, the Smithsonian would experience what Henry

called “interruptions” of its own programs. One

of Henry's first scientific endeavors as secretary was to

establish a national network of volunteer weather observers,

who would send monthly reports to the Smithsonian by mail

or telegraph. The war largely interfered with these means

of communication, especially hindering news from the South

and West. There would be other interruptions for sure, but

no event was as devastating as the Castle fire on January

24, 1865. An improperly installed stovepipe caused the fire,

which did extensive damage to the building and collections.

Worse still, most of the Smithsonian’s early records were

reduced to ashes. The building would be restored, and within

days the military had constructed a temporary roof. Yet the

bulk of Henry’s letters, some 85,000 pages, would be mostly

irretrievable. “In the space of an hour was thus destroyed

the labor of years,” wrote Mary Henry in her diary of

her father’s loss. Mary went on to record how the letters

had been “written with great care & were in answer

to questions upon almost every subject. . . . It is next to

losing Father to have them go.” Throughout

the conflict, the Smithsonian would experience what Henry

called “interruptions” of its own programs. One

of Henry's first scientific endeavors as secretary was to

establish a national network of volunteer weather observers,

who would send monthly reports to the Smithsonian by mail

or telegraph. The war largely interfered with these means

of communication, especially hindering news from the South

and West. There would be other interruptions for sure, but

no event was as devastating as the Castle fire on January

24, 1865. An improperly installed stovepipe caused the fire,

which did extensive damage to the building and collections.

Worse still, most of the Smithsonian’s early records were

reduced to ashes. The building would be restored, and within

days the military had constructed a temporary roof. Yet the

bulk of Henry’s letters, some 85,000 pages, would be mostly

irretrievable. “In the space of an hour was thus destroyed

the labor of years,” wrote Mary Henry in her diary of

her father’s loss. Mary went on to record how the letters

had been “written with great care & were in answer

to questions upon almost every subject. . . . It is next to

losing Father to have them go.”

|