|

|

|

|

|

inslow Homer (1836—1910) was twenty-five when the Civil War began in the spring of 1861. Although his native state of Massachusetts was recruiting thousands of men his age to serve in the Union army, Homer, as a special artist for Harper’s Weekly, was fortunate to have been able to pursue his chosen profession while satisfying his wanderlust for adventure much like a soldier. He was just beginning a lifelong career that would earn him fame and affluence for his paintings of American life and nature, especially of the sea. Already he was winning admirers through the pages of Harper’s with his sensitive wood engravings that portrayed the life of soldiers in camp and conveyed the longing of loved ones left behind. inslow Homer (1836—1910) was twenty-five when the Civil War began in the spring of 1861. Although his native state of Massachusetts was recruiting thousands of men his age to serve in the Union army, Homer, as a special artist for Harper’s Weekly, was fortunate to have been able to pursue his chosen profession while satisfying his wanderlust for adventure much like a soldier. He was just beginning a lifelong career that would earn him fame and affluence for his paintings of American life and nature, especially of the sea. Already he was winning admirers through the pages of Harper’s with his sensitive wood engravings that portrayed the life of soldiers in camp and conveyed the longing of loved ones left behind.

Homer was mostly a self-taught artist whose talent was readily apparent from the start of his career. It was matched by his determination to develop his skills independently and to his own liking. As evidence of this, Homer declined to join the staff of Harper’s, preferring instead to contribute to the paper as a freelance artist. For Homer, the Civil War provided an unusual opportunity to explore and practice the nuances of his profession, while rendering a service to those who valued his art as a documentary of the war.

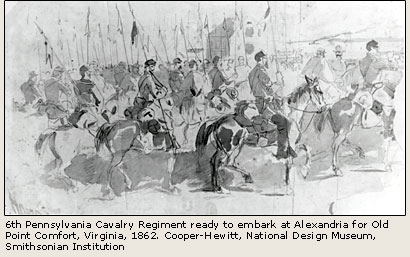

Between 1861 and 1865, Homer made several trips to the war front in Virginia. Armed with a letter from Fletcher Harper, the editor of Harper’s Weekly, identifying him as a “special artist,” Homer was able to move through the lines and gain access to the Army of the Potomac. Early in April 1861, he was in Alexandria and witnessed the embarkation of the army aboard steamers that would ferry it to the Peninsula near Richmond in preparation for General George B. McClellan’s long-awaited spring offensive. A drawing he made of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry—the only Union regiment to carry lances—gave witness to Homer's eye for the unusual and the dramatic.

Homer sailed with the army down the Potomac toward Fortress Monroe and Yorktown in the Tidewater region. With his drawing supplies of pen and pencil, gray wash, and white paper, Homer stayed with the army for about two months, during which time the siege of Yorktown took place and the Battle of Fair Oaks was fought. Except for what can be delineated in his drawings, Homer never kept records of his movements. Yet the correspondence of an acquaintance, Lieutenant Colonel Francis Channing Barlow of the 61st New York Infantry, indicated that the artist camped, at least temporarily, with the 61st. Homer subtly made this association himself in at least two of his works, in which the number “61” appears on a knapsack. Based on evidence in two other works—the paintings The Briarwood Pipe (1864) and Pitching Horseshoes (1865)—Homer at some point also came in contact with the 5th New York Infantry, also known as “Duryee’s Zouaves.” Labeled “the best disciplined and soldierly regiment in the Army” by General McClellan, they wore distinctive Zouave uniforms of bright red pantaloons, red fezzes, and dark blue collarless jackets. Homer made sketches of these colorfully clad soldiers, fully realizing that this work had a potential for “future greatness.” Homer sailed with the army down the Potomac toward Fortress Monroe and Yorktown in the Tidewater region. With his drawing supplies of pen and pencil, gray wash, and white paper, Homer stayed with the army for about two months, during which time the siege of Yorktown took place and the Battle of Fair Oaks was fought. Except for what can be delineated in his drawings, Homer never kept records of his movements. Yet the correspondence of an acquaintance, Lieutenant Colonel Francis Channing Barlow of the 61st New York Infantry, indicated that the artist camped, at least temporarily, with the 61st. Homer subtly made this association himself in at least two of his works, in which the number “61” appears on a knapsack. Based on evidence in two other works—the paintings The Briarwood Pipe (1864) and Pitching Horseshoes (1865)—Homer at some point also came in contact with the 5th New York Infantry, also known as “Duryee’s Zouaves.” Labeled “the best disciplined and soldierly regiment in the Army” by General McClellan, they wore distinctive Zouave uniforms of bright red pantaloons, red fezzes, and dark blue collarless jackets. Homer made sketches of these colorfully clad soldiers, fully realizing that this work had a potential for “future greatness.”

“Future greatness.” That was how Homer’s mother

described her son and his activities in the fall of 1861. Mrs.

Homer’s confidence evokes the self-assuredness of the artist

himself. While lasting fame still awaited him, Homer studiously

used the backdrop of the Civil War as a practice canvas upon

which to record a series of his impressions, a few of which

have become iconic images of the common soldier. Many of his

sketches would of course appear as wood engravings in Harper’s.

Still dozens more would become study-vignettes for future paintings,

some of which he put on exhibition and offered for sale.

The Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, in New York City owns more than three dozen of Homer’s original Civil War sketches. These form part of a larger collection of 287 drawings donated by Homer’s brother, Charles Savage Homer Jr., in 1912, two years after Winslow’s death. The drawings, many of them rough sketches, are indicative of how Homer worked to compile a portfolio of images for future use. While his artistic skill is clearly evident, these drawings reveal the early work of a man with great ambitions who would become one of America’s most acclaimed artists.

|

|

|